Basic Thermodynamic Devices

Thermodynamic devices play a crucial role in various engineering applications, from power generation to refrigeration and heating systems. These devices are designed to control energy transfer, pressure, and temperature through various mechanical and thermal processes. This article explores essential thermodynamic devices and their fundamental functions.

What is an ideal gas in simple words?

Before discussing thermodynamic devices, it is important to first understand the concept of an Ideal Gas. An ideal gas is a hypothetical gas l consisting of numerous randomly moving point particles that do not interact with one another. An ideal gas is a simplified model of gases that obeys the Ideal Gas Law:

PV=nRT

where P is pressure, V is volume, n is the number of moles, R is the universal gas constant, and T is temperature.

Key Characteristics of an Ideal Gas:

Is this possible? Not really! However, we can get very close to such behavior at very low density.

- Gas molecules have negligible volume.

- No intermolecular forces act between molecules.

- Collisions are perfectly elastic.

- The model is most accurate at high temperatures and low pressures.

What is the internal energy of an ideal gas?

The internal energy of an ideal gas depends only on temperature and is unaffected by pressure or density. It represents the total kinetic energy of gas particles resulting from their random motion. Likewise, both internal energy and enthalpy in an ideal gas are solely temperature-dependent. Since there are no intermolecular forces, changes in volume or pressure do not affect internal energy, making temperature the key determining factor.

Δu=cv(T2−T1)

Δh=cp(T2−T1)

where cv and cp are the specific heat capacities at constant volume and pressure, respectively. Using constant specific heat is only valid for small temperature ranges and is generally not a reliable assumption for ideal gases. This approach is applicable only when cv and cp remain constant or nearly constant over the given temperature range.

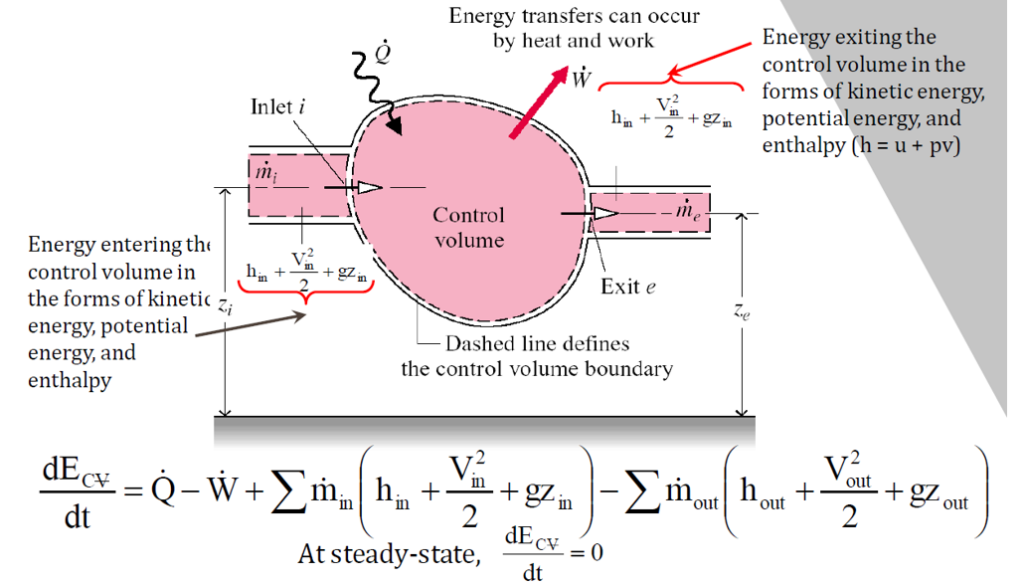

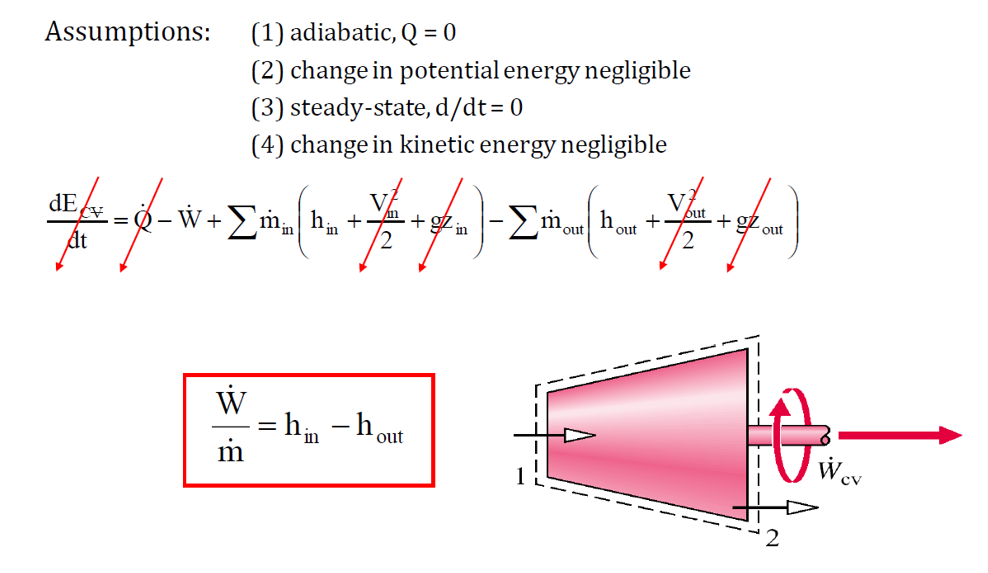

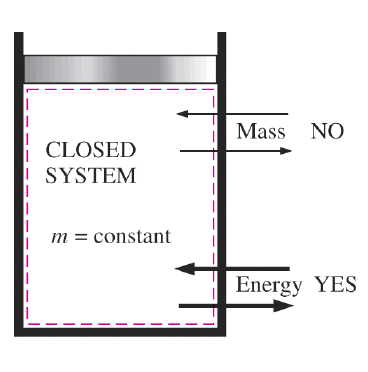

Control Volume: Open System

A control volume is a thermodynamic system where both mass and energy can cross their boundaries, unlike a closed system, where mass remains constant. The key distinction of a control volume is the presence of mass flow across the system boundary, making it an open system.

In an open system, energy exchange occurs not only through work and heat transfer but also through flow energy, which accounts for the movement of mass in and out of the system. Since mass can enter, exit, or both, the system is typically defined by a fixed volume, within which energy interactions take place.

heat exchanger.

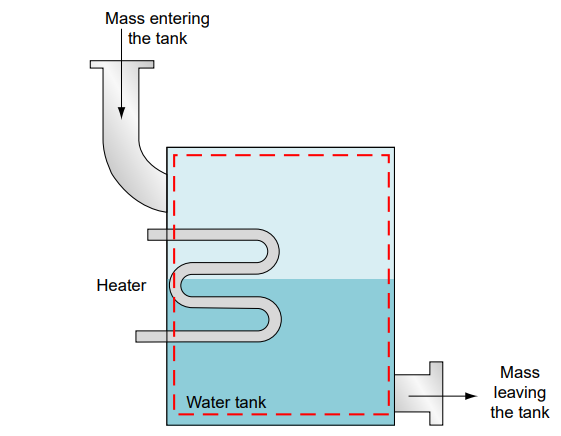

A common example of a control volume is a water tank where water enters from the top, exits from the bottom and is heated to produce hot water. The dashed boundary around the tank represents the control volume, encompassing the internal space where mass and energy interactions occur. The First Law of Thermodynamics for an open system is:

where:

- Q_dot = heat transfer rate

- W_dot= work transfer rate

- m_dot= mass flow rate

- h = enthalpy per unit mass

Examples of open systems include heat exchangers, turbines, and compressors, where energy and mass continuously flow in and out.

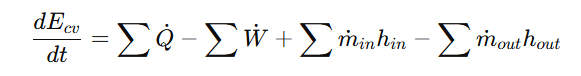

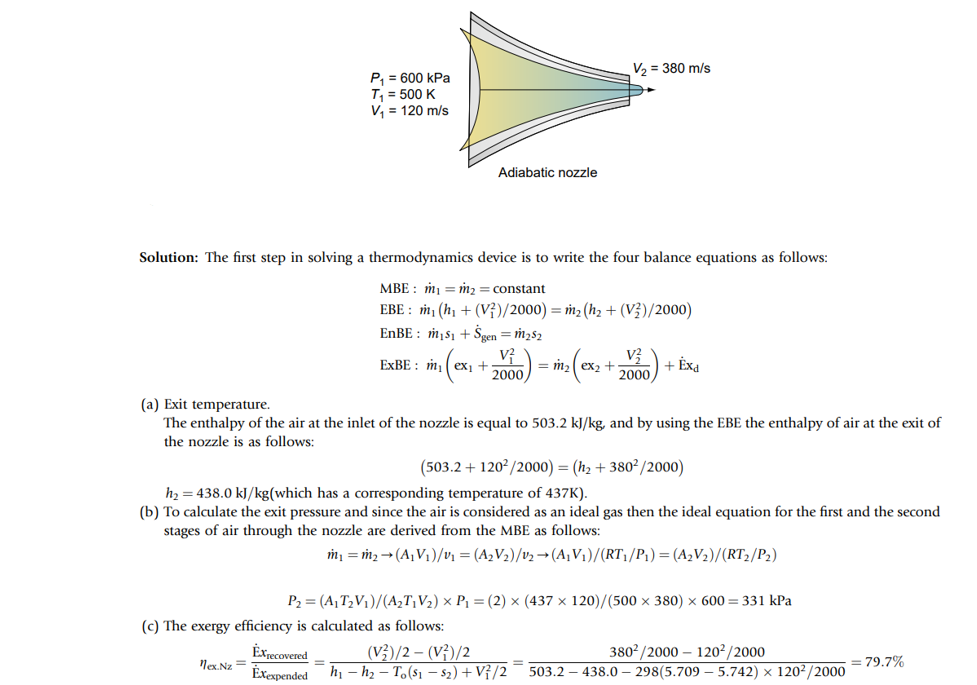

What is the working principle of nozzle and diffuser?

The working principle of a nozzle and a diffuser is based on controlling fluid velocity and pressure through a variable cross-sectional area. A nozzle accelerates fluid by reducing pressure, causing a drop in enthalpy, which is converted into increased velocity. In contrast, a diffuser slows down the fluid, leading to a rise in pressure as the flow expands. Both devices are essential in applications such as jet engines, steam turbines, and HVAC systems, where precise control of fluid dynamics is required.

where:

- h = enthalpy

- V = velocity

Nozzle vs diffuser summary:

- A nozzle increases velocity while decreasing pressure by constricting flow.

- A diffuser decreases velocity while increasing pressure by expanding flow.

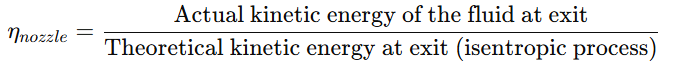

What is the nozzle efficiency?

Nozzle efficiency is a measure of how effectively a nozzle converts pressure energy into kinetic energy. It compares the performance of a real nozzle to an ideal, isentropic nozzle operating under the same pressure conditions.

Mathematically, nozzle efficiency (ηnozzle) is defined as:

Since real nozzles experience losses due to friction and other inefficiencies, the actual kinetic energy at the exit is always lower than in an ideal case. Nozzle efficiency helps in evaluating and improving the performance of fluid flow systems.

Basic Flow Devices with No Moving Parts

Some devices are simply pipes through which the working substance flows. These include:

- Throttle / Valve: Constriction in a pipe that reduces pressure.

- Diffuser: Converts kinetic energy into pressure by expanding the flow.

- Nozzle: Converts pressure into kinetic energy or measures flow rate by restricting flow.

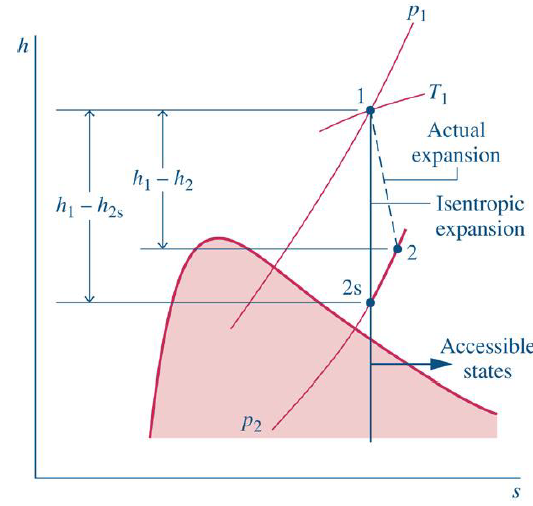

Nozzles – Example Problem

Consider that an adiabatic nozzle, as shown in the picture below, has accelerating steam entering with a pressure of 600 kPa, at a temperature of 500K, and with a velocity of 120 m/s. The adiabatic nozzle has a cross-sectional area ratio of 2:1, which will result in an exit velocity of 380 m/s. Calculate (a) the exit temperature, (b) the exit pressure, and (c) the exergy efficiency of the process.

Turbines, Pumps, and Compressors

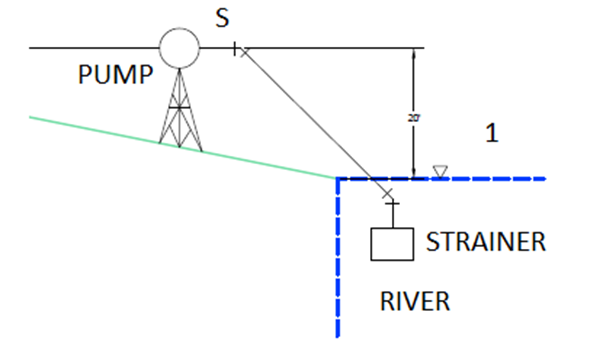

A turbine is a device that generates power by utilizing fluid flow to drive a set of blades, causing a shaft to rotate and produce mechanical work. In contrast, a compressor requires work input to increase the pressure of a gas, enabling its flow. Similarly, a pump operates like a compressor but is designed for liquids, using work to raise pressure or elevation to facilitate movement. These devices are essential for energy conversion in thermodynamic cycles.

Turbines:

- Extract energy from fluid flow to generate mechanical work.

- Used in power plants and jet engines.

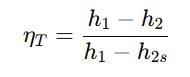

- Governed by isentropic efficiency:

where h2s is the ideal exit enthalpy for an isentropic (reversible) process.

Pumps and Compressors:

- Pumps increase pressure in liquids.

- Compressors increase pressure in gases.

- They require work input and are evaluated using efficiency:

where h2 is the actual enthalpy at the compressor or pump exit. These devices are essential in refrigeration, air compression, and fluid transportation.

What is the efficiency of the compressor and turbine?

The efficiency of a compressor and a turbine is determined by comparing their actual performance to that of an ideal, isentropic device operating between the same pressure limits.

Turbine Efficiency (ηT)

A turbine extracts energy from a high-pressure fluid to generate work output. However, due to losses such as friction and heat transfer, the actual power generated is always less than the ideal power. ηT=Actual Work Output/ Isentropic Work Output

A higher turbine efficiency means more useful energy is extracted from the fluid, improving overall system performance.

Compressor Efficiency (ηC)

In the case of liquids, a compressor (or pump) requires work input to increase fluid pressure. In reality, due to inefficiencies like mechanical losses and heat generation, the actual work required is greater than the ideal work. ηC=Isentropic Work Input/Actual Work Input

A higher compressor efficiency means less energy is wasted, reducing the power required to achieve the desired pressure increase.

Both turbine and compressor efficiencies play a crucial role in thermodynamic cycles such as the Brayton cycle (jet engines) and Rankine cycle (steam power plants), where optimizing efficiency leads to better performance and energy savings.

Flow Devices with Moving Components for Work Output:

- Turbine: Converts high-pressure fluid into mechanical work. Often approximated as adiabatic.

- Expander: A turbine where heat transfer is nontrivial.

Flow Devices with Moving Components for Work Input:

- Compressor: Uses mechanical work to increase pressure.

- Pump: A compressor for liquids.

- Fan / Blower: Moves air or gas using mechanical work.

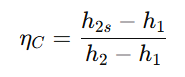

Turbine- Example Problem

Consider an adiabatic steam turbine below, with the following inlet and exit states:: P1= 12,000 kPa,

T1= 625C, P2 = 10 kPa, x2= 0.95. Taking the dead-state temperature of steam as sa aturated liquid at 25C, determine the isentropic efficiency and exergy efficiency of the steam turbine.

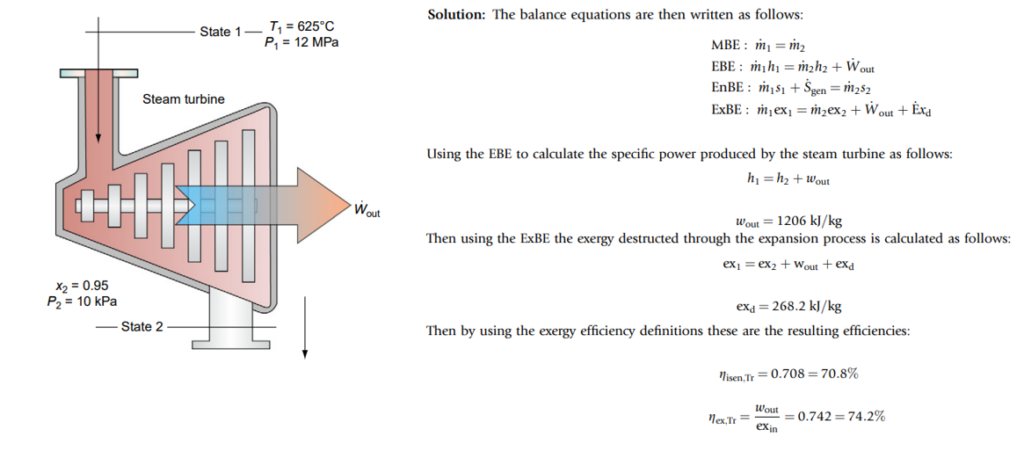

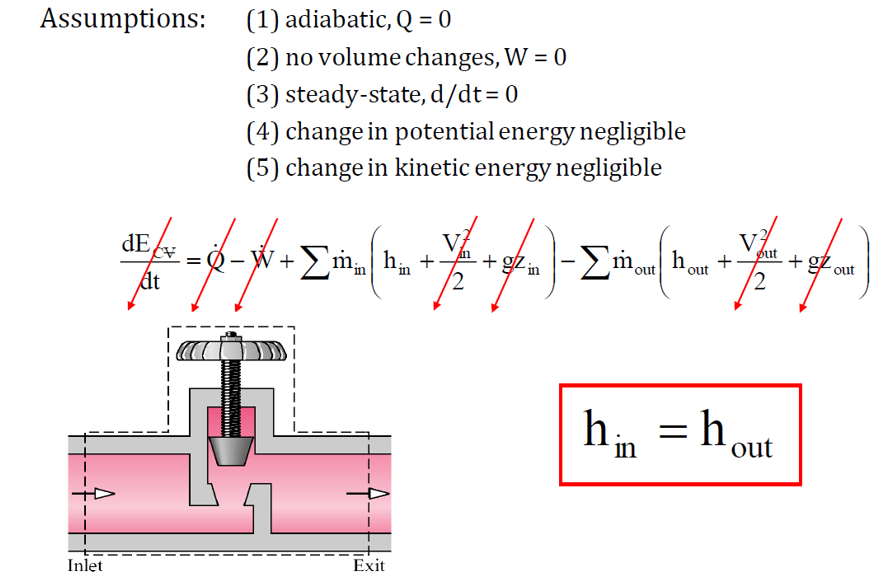

What is the purpose of the throttling valve?

A throttling valve, also known as a control valve or throttle control valve, is a device used to reduce fluid pressure without performing work. It regulates flow by creating a restriction, causing a pressure drop while maintaining constant enthalpy. These valves are widely used in industries such as oil and gas, chemical processing, and water treatment to control fluid flow and pressure within a system.

Throttling Process Assumptions:

- No work done (W=0).

- No heat transfer (Q=0).

- Negligible kinetic and potential energy changes.

Applying the First Law of Thermodynamics: h1=h2

Since enthalpy remains constant, throttling leads to a temperature drop, making it essential for refrigeration and air conditioning systems.

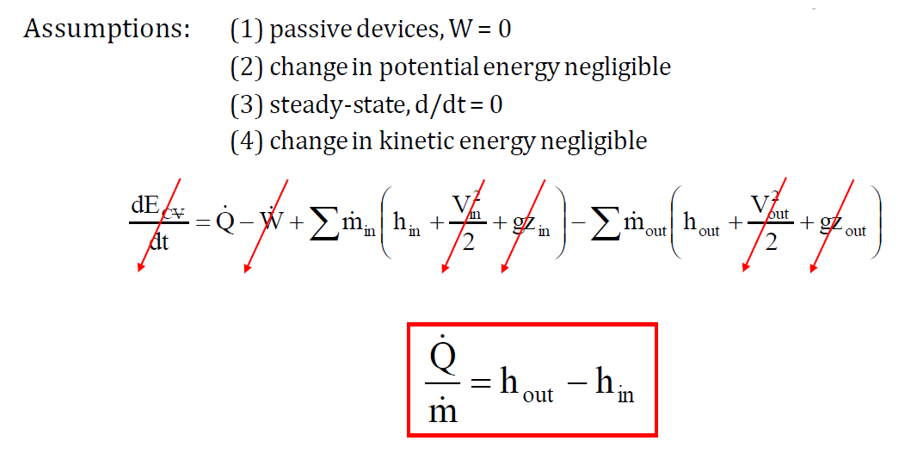

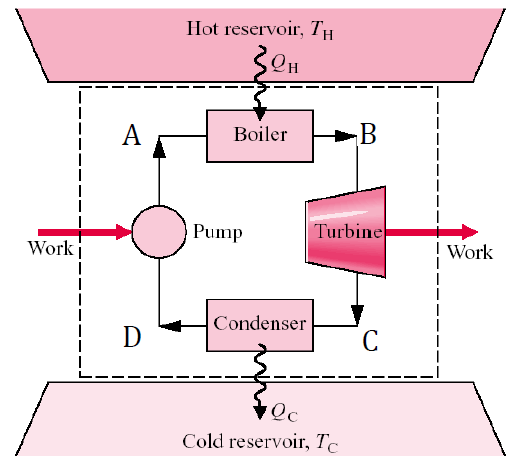

Boilers, Condensers, and Evaporators

In thermodynamics, boilers, condensers, and evaporators are heat exchangers that facilitate phase changes in fluids. Boilers convert liquids into vapor by adding heat, commonly used in power plants, heating systems, and industrial processes. Condensers remove heat from vapor to condense it into a liquid, essential in refrigeration systems, power plants, and industrial applications. Evaporators absorb heat to vaporize a liquid, playing a crucial role in refrigeration, heat pumps, and distillation. These devices are fundamental to energy conversion and thermal management systems across various industries.

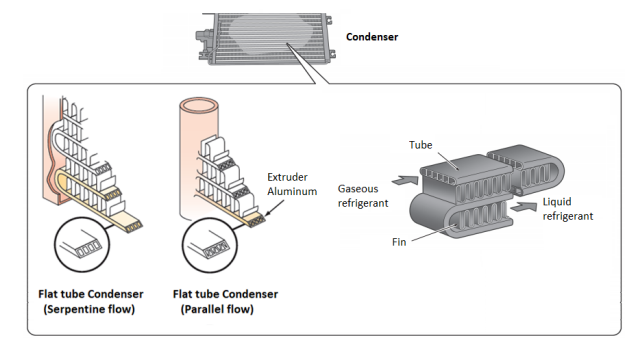

What does a condenser do in a cooling system?

In a cooling system, the condenser plays a critical role in removing heat from the refrigerant, converting it from a high-pressure gas to a liquid state. After the compressor increases the refrigerant’s pressure and temperature, the hot refrigerant gas enters the condenser, where it releases heat to the surrounding air through metal tubes and cooling fins. As the refrigerant cools down, it transitions from a gaseous to a liquid state, a process known as sub-cooling, ensuring efficient heat rejection.

Condensers are designed in various forms, such as serpentine and parallel-flow designs, to optimize heat transfer. In an automobile they are usually placed in front of the radiator to maximize exposure to airflow, enhancing cooling efficiency. By efficiently removing heat, the condenser ensures the refrigerant is properly cooled and prepared for the evaporation cycle, maintaining effective cooling in HVAC systems, refrigeration units, and automotive climate control systems.

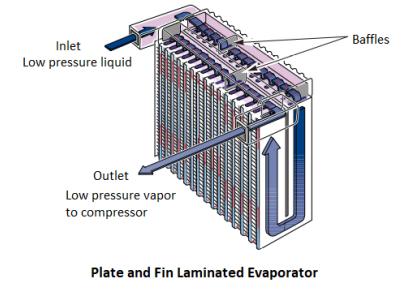

Where is the evaporator in a car?

The evaporator is a crucial component of the automotive climate control system, it is typically located inside the dashboard, within the passenger compartment. It is a heat exchanger that absorbs heat from the cabin air or incoming fresh air, cooling it before it is circulated inside the vehicle. The evaporator works by allowing the high-pressure liquid refrigerant, injected through an expansion valve or orifice tube, to expand and absorb heat, converting it into a low-temperature, low-pressure vapor.

As warm air passes over the cold evaporator fins, moisture in the air condenses and drains out through tubes underneath the vehicle, a process known as dehumidification. This helps improve passenger comfort and also reduces windshield fogging in humid conditions. Since the evaporator is hidden behind the dashboard, replacing it can be labor-intensive and requires a full system recharge.

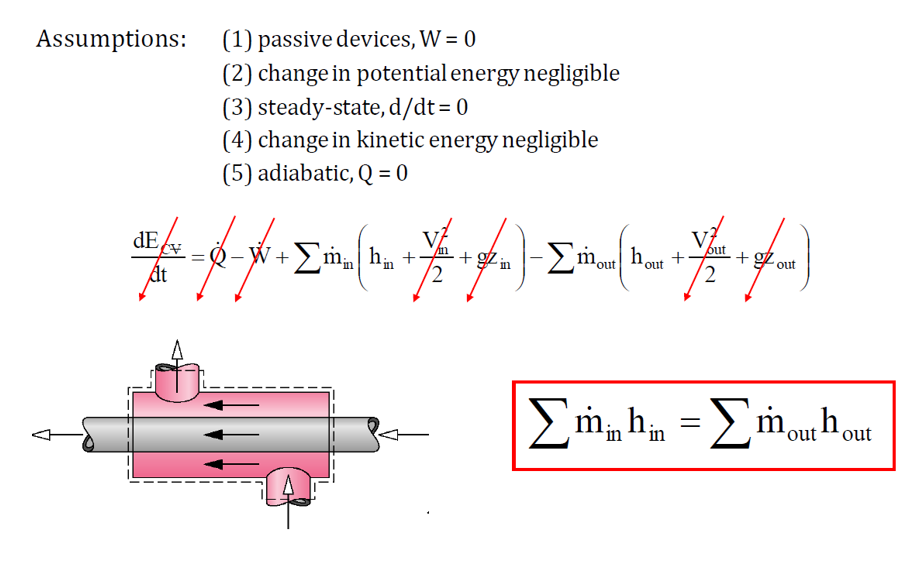

What is the purpose of the heat exchanger?

A heat exchanger is a device designed to transfer heat between two or more fluids without mixing them. It facilitates the exchange of thermal energy between a heat source and a working fluid, playing a key role in both cooling and heating processes. The fluids involved may be either separated by a solid barrier to prevent mixing or allowed to interact directly.

Heat exchangers are extensively used in HVAC systems, power plants, chemical processing, petroleum refining, natural gas treatment, and sewage processing. A common example is the radiator in an internal combustion engine, where engine coolant flows through coils while air passes over them, dissipating heat. Another example is a heat sink, a passive heat exchanger that transfers heat from electronic or mechanical components to a cooling medium like air or liquid.

The energy balance for a heat exchanger is:

Common types of heat exchangers include:

- Shell-and-tube heat exchangers (used in power plants).

- Plate heat exchangers (found in HVAC systems).

- Fin-tube heat exchangers (used in radiators and air conditioners).

Basic Heat Transfer Devices Overview:

These devices are primarily used for heat exchange rather than mechanical work:

- Boiler / Evaporator / Steam Generator: Turns liquid into vapor.

- Heater: Generic term for devices that add heat.

- Condenser: Removes heat from vapor to condense it.

- Combustor: Burns fuel to add heat to a system.

Devices That Produce Work:

- Heat Engine: Converts thermal energy into mechanical work (e.g., internal combustion engine inside of a car).

Devices That Use Work to Move Heat:

- Heat Pump: Uses work to move heat from cold to hot (e.g., heating a house in winter).

- Refrigerator: Removes heat from a cold space (e.g., keeping milk cold).

- Air Conditioner (A/C): Removes heat from a building’s interior to the outside.

Conclusion

Thermodynamic devices play a fundamental role in energy transfer and conversion across various engineering applications. From nozzles and diffusers that regulate fluid velocity and pressure to turbines, compressors, and pumps that manage mechanical work, each device operates based on core thermodynamic principles.

Heat exchangers, including boilers, condensers, and evaporators, facilitate efficient thermal management while throttling valves control fluid pressure without performing work. Understanding these devices is essential for optimizing power generation, refrigeration, HVAC systems, and industrial processes. By applying thermodynamic principles, engineers can enhance efficiency, sustainability, and performance in real-world energy systems.

Glad to be one of several visitants on this awing internet site : D.