Understanding Thermodynamic Cycles

Thermodynamic cycles are fundamental principles in engineering, establishing the basis for the operation of power plants, internal combustion engines, refrigerators, and air conditioners. These cycles describe the processes a working fluid undergoes to convert heat into work or vice versa. This article explores various thermodynamic cycles, including basic, Carnot, Rankine, Otto, Diesel, Brayton, refrigeration, and vapor-compression cycles.

What are the basic thermodynamic cycles?

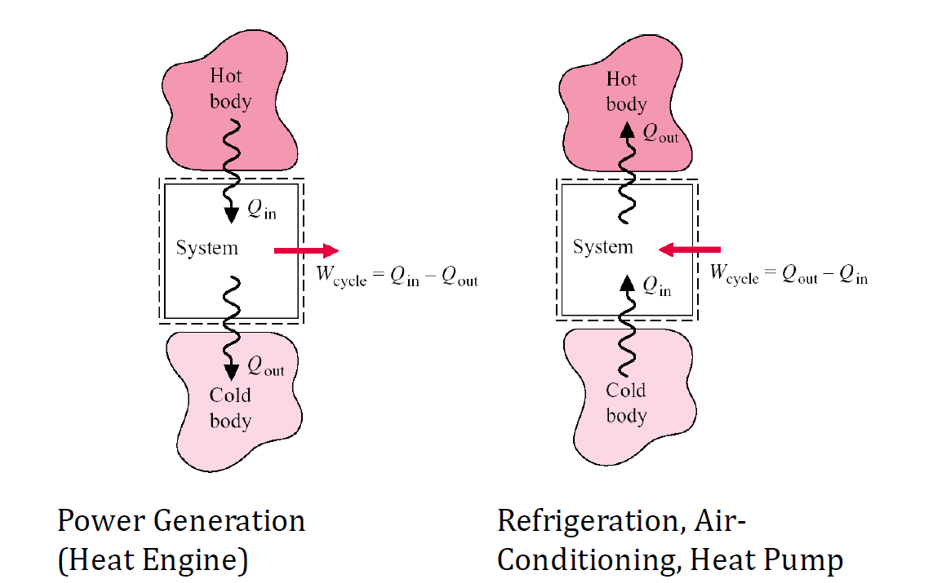

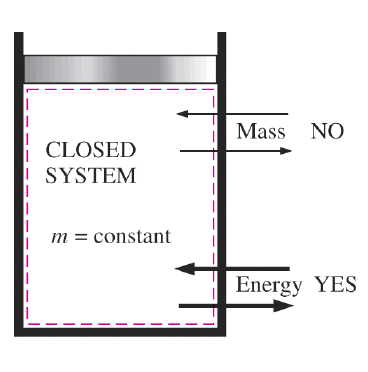

Thermodynamic cycles are processes that return a system to its initial state. These cycles are categorized into two primary classes: power cycles and heat pump cycles.

Power Cycles:

- Power cycles convert heat energy into mechanical work output.

- They are commonly used in internal combustion engines and power plants.

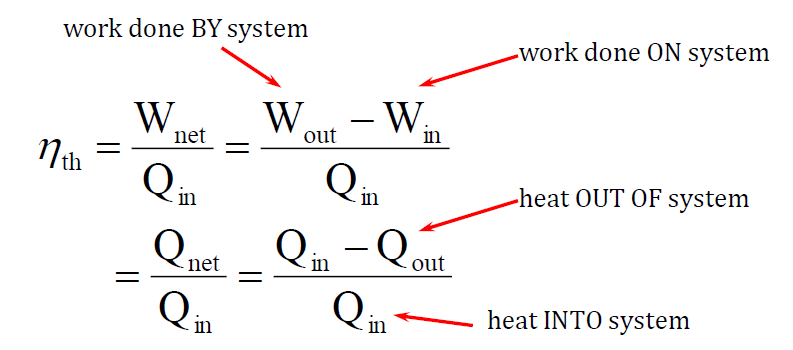

- The performance of a power cycle is measured by thermal efficiency, which is the ratio of useful work output to the energy input required to run the cycle.

Heat Pump Cycles:

- Heat pump cycles transfer heat from a lower-temperature region to a higher-temperature region using mechanical work as the input.

- These cycles are found in refrigerators, air conditioners, and heat pumps for space heating.

Both types of cycles involve a series of processes that bring the system back to its original state, ensuring continuous operation.

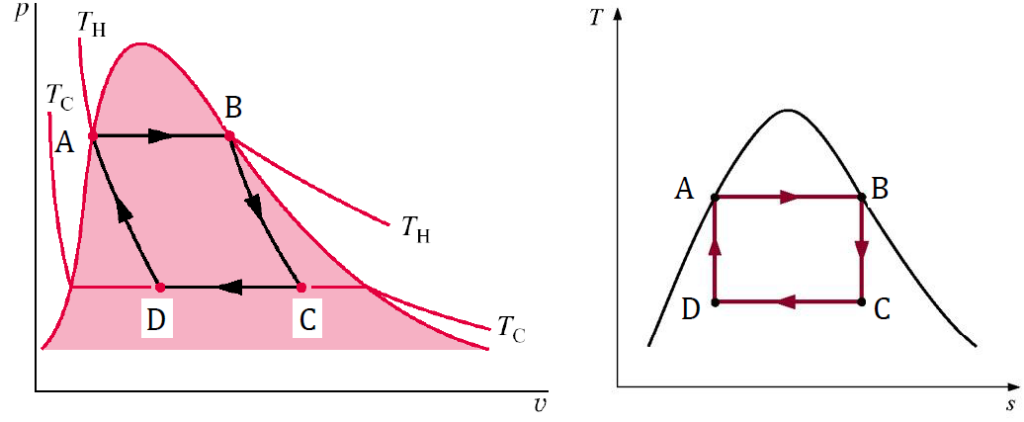

What is the Carnot cycle in simple terms?

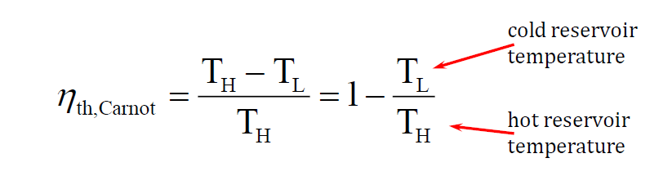

The Carnot cycle is a theoretical thermodynamic cycle that defines the maximum possible efficiency a heat engine can achieve. It is considered ideal because it operates with no irreversibilities and consists of reversible processes.

The Carnot cycle represents the best possible performance for a heat engine operating between two temperature reservoirs. Since it is completely reversible, it establishes an upper limit on efficiency, meaning no real engine can be more efficient than a Carnot engine operating between the same temperatures.

Although it is not practical for real-world applications due to the difficulty of achieving perfectly reversible processes, it is a benchmark for evaluating and improving actual heat engine designs.

- A to B: isothermal evaporation of saturated liquid to saturated vapor

- B to C: isentropic expansion of vapor (Q = 0; ∆s = 0)

- C to D: isothermal condensation of vapor

- D to A: isentropic compression of vapor (Q = 0; ∆s = 0)

Carnot Efficiency:

The Carnot efficiency is theoretical and has limited practical application. It represents the maximum possible efficiency of an idealized engine. However, even if such an engine could be built, it must operate at extremely slow speeds to allow heat transfer. While it would achieve high efficiency, it would produce no usable power, making it impractical for real-world applications. Carnot efficiency can be calculated with the following equation:

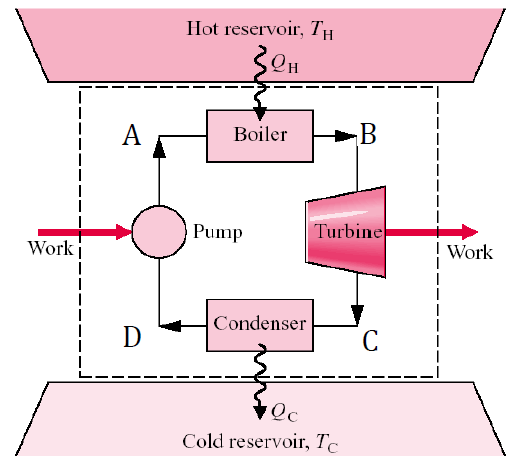

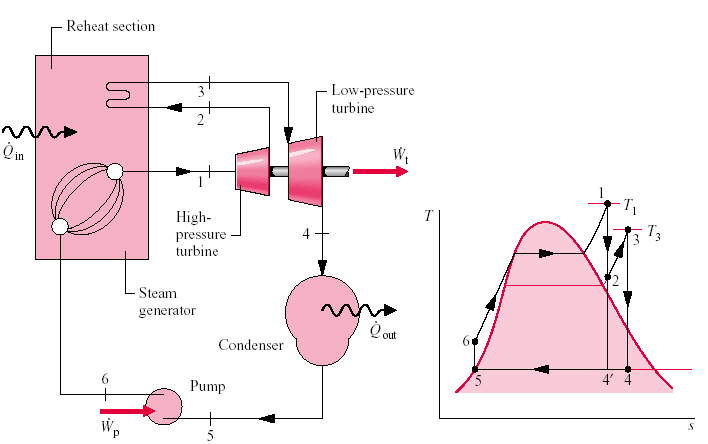

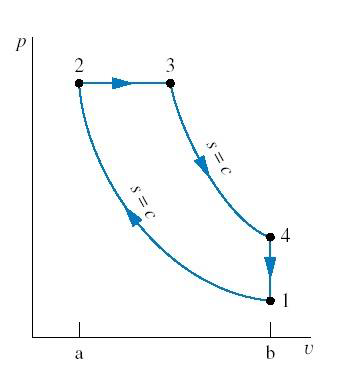

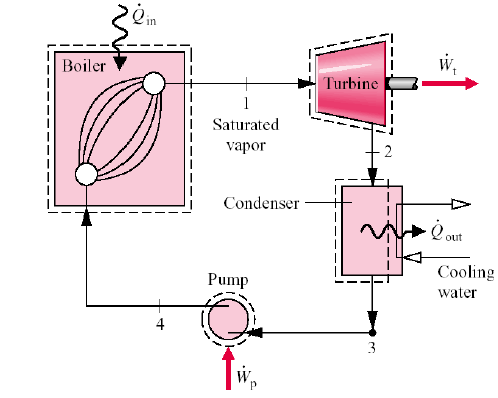

Rankine Cycle: The Foundation of Power Plants

The Rankine cycle is the most widely used thermodynamic cycle for steam power plants, where water is the working fluid. It operates by pressurizing water, heating it to generate superheated steam, expanding the steam through a turbine to produce power, and then cooling it back into water for recirculation. This continuous process efficiently converts heat into mechanical work, making the Rankine cycle essential for electricity generation in steam-based power systems.

- 1 to 2: Isentropic expansion of the working fluid through the turbine from saturated vapor at state 1 to the condenser pressure (Q = 0; ∆s = 0)

- 2 to 3: Heat transfer from the working fluid as it flows at constant pressure through the condenser with saturated liquid at state 3

- 3 to 4: Isentropic compression in the pump to state 4 in the compressed liquid region. (Q = 0; ∆s =0)

- 4 to 1: Heat transfer to the working fluid as it flows at constant pressure through the boiler to complete the cycle

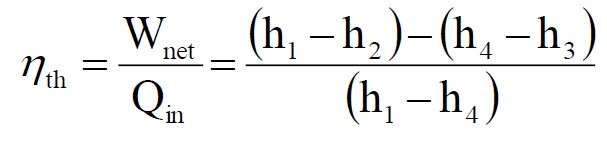

What is the efficiency of a Rankine cycle?

The efficiency of a Rankine cycle depends on factors such as reheat cycles, parasitic losses, and non-idealities in components like pumps and turbines. A typical Rankine cycle has a thermal efficiency of about 30.4%, with minimal variation. Although theoretical efficiencies of around 60% are possible, real-world constraints prevent most systems from reaching this level. Efficiency is the ratio of useful output to

Required input:

Despite being less efficient than the Carnot cycle, the Rankine cycle remains the most widely used thermodynamic cycle for electricity generation, with improvements such as reheat cycles helping optimize performance.

What is the effect of superheated steam in a Rankine cycle?

Superheated steam plays a crucial role in improving the efficiency and durability of a Rankine cycle. By increasing the temperature of the working fluid before it enters the low-pressure turbine, superheating reduces moisture content at the turbine exit, which helps prevent blade erosion and wear. Additionally, superheating increases both the network output and the heat input, leading to an overall increase in thermal efficiency.

This is because the average temperature of heat addition is higher, allowing for better energy conversion. Superheating contributes to optimizing performance by enhancing efficiency and prolonging turbine lifespan.

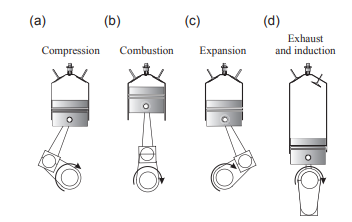

What is the Otto cycle?

The Otto cycle is the ideal model for spark-ignition engines, such as those used in gasoline-powered cars. Named after Nikolaus A. Otto, it was utilized in the successful four-stroke engine he built in 1876 in Germany. The concept was originally proposed by French engineer Beau de Rochas in 1862.

The Otto cycle is a thermodynamic cycle that describes the operation of spark-ignition internal combustion engines. It is an air-standard cycle that approximates the processes occurring in gasoline-powered engines. The cycle consists of isentropic compression and expansion, constant volume heat addition (combustion), and heat rejection.

(c) expansion (d) exhaust and induction.

What are the 4 stages of the Otto cycle?

Unlike the Diesel cycle, which involves heat addition at constant pressure, the Otto cycle assumes that combustion occurs instantly at a constant volume. This cycle is commonly used to model the efficiency and performance of gasoline engines, providing insight into how they convert fuel into mechanical work. It consists of:

working fluid to simplify the chemistry due to combustion

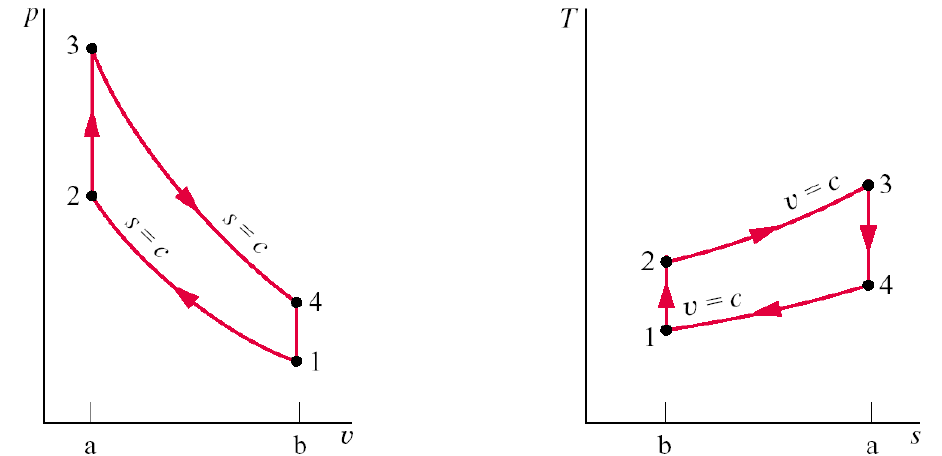

- 1 to 2: Isentropic compression of the working fluid (Q = 0; ∆s = 0).

- 2 to 3: Constant volume heat addition.

- 3 to 4: Isentropic expansion of the working fluid (Q = 0; ∆s = 0).

- 4 to 1: Constant volume heat rejection.

The efficiency of an Otto cycle depends on the compression ratio, which is the ratio of the cylinder’s volume before and after compression.

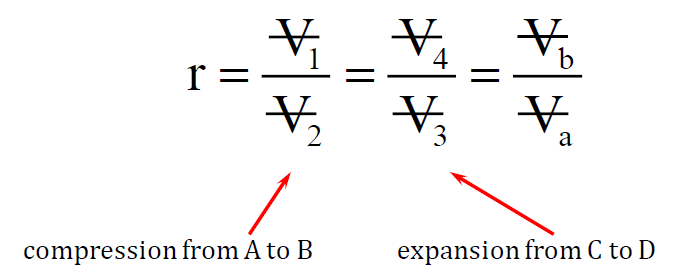

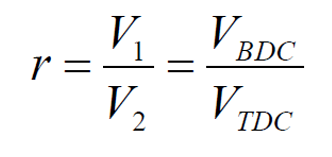

What is the compression ratio in the Otto cycle?

The compression ratio (r) in the Otto cycle is defined as the ratio of the cylinder volume at bottom dead center (BDC) to the volume at top dead center (TDC):

where:

- V1 is the volume at BDC (when the piston is at its lowest point).

- V2 is the volume at TDC (when the piston is at its highest point).

The compression process in the Otto cycle requires mechanical work to be added to the working gas. Typically, gasoline engines operate with a compression ratio of around 9:1 – 10:1. A higher compression ratio generally improves engine efficiency by increasing the thermal efficiency of the cycle.

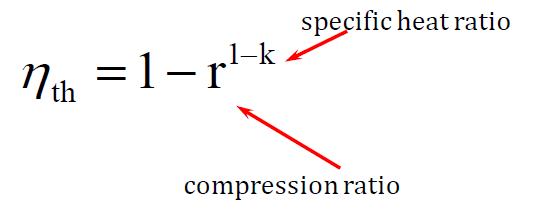

How do you calculate the efficiency of an Otto cycle?

The thermal efficiency (ηth) of an Otto cycle, which is used in spark-ignition internal combustion engines, is calculated using the following formula:

This formula shows that higher compression ratios result in higher efficiency. Since Otto cycle engines typically have compression ratios between 9:1 and 10:1, this ratio significantly affects their thermal efficiency, making compression an important factor in engine performance.

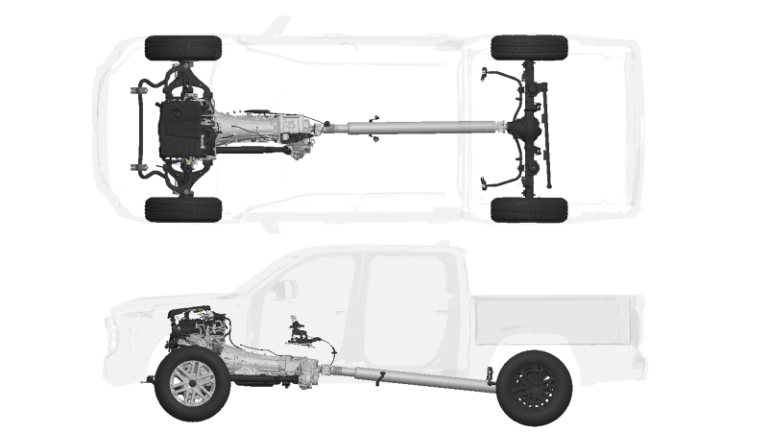

What is the diesel cycle process?

The compression-ignition engines were first proposed by Rudolph Diesel in the 1890s. The Diesel cycle is a thermodynamic cycle used in compression-ignition (CI) engines, commonly found in diesel-powered vehicles and machinery. The idealized Diesel cycle assumes the working fluid behaves as an ideal gas and simplifies the process by ignoring combustion chemistry and exhaust-recharge procedures. It consists of four distinct processes, with a key feature being constant pressure heat addition:

- Isentropic Compression (1 → 2):

- The working fluid (air) is compressed adiabatically, meaning no heat is exchanged.

- This compression significantly increases the temperature of the air.

- Constant Pressure Heat Addition (2 → 3):

- Fuel is injected and ignited due to the high temperature of the compressed air.

- The heat addition occurs at constant pressure, unlike the Otto cycle (gasoline engines), where it happens at constant volume.

- Isentropic Expansion (3 → 4):

- The heated gas expands adiabatically, performing work on the piston to generate mechanical output.

- This expansion results in a drop in temperature and pressure.

- Constant Volume Heat Rejection (4 → 1):

- The cycle completes as heat is rejected at constant volume, returning the system to its initial state.

Carnot P-v and T-s Diagrams

Below is the example of the P-v on the left and the T-s diagram on the right.

What is the efficiency of the diesel cycle?

The efficiency of the Diesel cycle is higher than that of the Otto cycle due to its higher compression ratio, which enhances thermal efficiency and fuel economy. In practical applications, Diesel engines can achieve compression ratios of up to 20, resulting in thermal efficiencies as high as 64.7%.

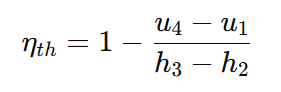

The equation gives the thermal efficiency (ηth) of the Diesel cycle:

where:

- u4−u1 represents the heat rejected in the cycle.

- h3−h2 represents the heat added at constant pressure.

Since higher compression ratios improve efficiency by increasing the temperature and pressure of the working fluid before combustion, Diesel engines typically operate more efficiently than gasoline engines. This makes them ideal for heavy-duty applications such as trucks, pod propulsion systems used on ships, and locomotives.

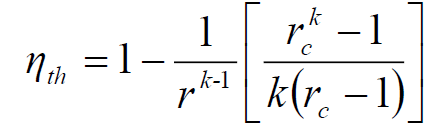

What is the thermal efficiency of a cold air standard diesel cycle?

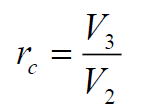

Under the cold air standard assumption, the thermal efficiency of a Diesel cycle is determined by two key parameters:

- Compression ratio (r) – the cylinder volume ratio before and after compression.

- Cutoff ratio (rc) – the ratio of cylinder volume after heat addition to the volume before heat addition.

The thermal efficiency (ηth) of the cold air standard Diesel cycle is given by the formula:

where:

- k is the ratio of specific heats (Cp/Cv), typically around 1.4 for air.

Cold Air Standard Assumption

- The working fluid (air) is treated as an ideal gas.

- Specific heats (Cp and Cv) are constant and evaluated at room temperature.

- This simplifies the Diesel cycle analysis while maintaining reasonable accuracy for estimating efficiency.

Since higher compression ratios improve efficiency, Diesel engines tend to be more efficient than gasoline engines. However, the cutoff ratio introduces a dependency on the extent of heat addition, meaning efficiency is optimized when the right balance between r and rc is achieved.

Which best describes the Brayton cycle?

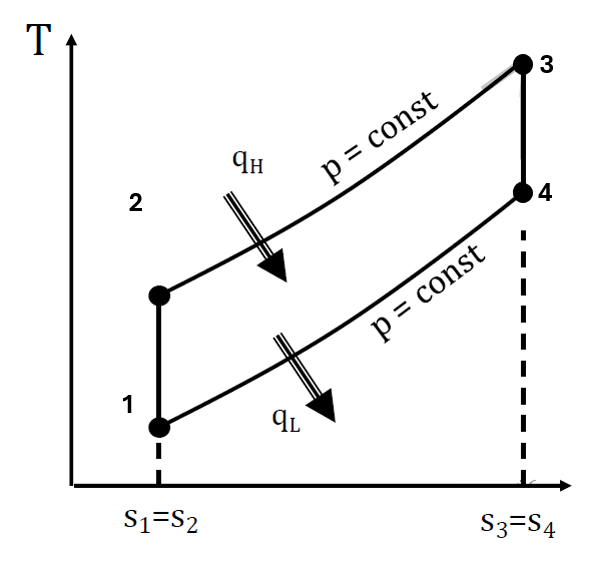

The Brayton cycle is the fundamental thermodynamic cycle used in gas turbines and jet engines. It consists of isentropic (adiabatic) compression, expansion, constant pressure heat addition, and rejection. The cycle follows these key steps:

- Isentropic Compression – A gas is compressed adiabatically in a compressor, increasing its temperature and pressure.

- Constant Pressure Heat Addition – Heat is added at constant pressure, typically through fuel combustion, further raising the gas temperature.

- Isentropic Expansion – The high-energy gas expands adiabatically through a turbine, producing work.

- Constant Pressure Heat Rejection – The gas is cooled at constant pressure, returning to its initial state.

In most applications, the compressor and turbine are mounted on the same shaft, allowing the turbine to drive the compressor while also producing useful work. The Brayton cycle is widely used in aviation and power generation due to its efficiency and ability to operate at high temperatures and pressures.

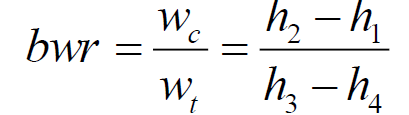

What Is the Back Work Ratio for the Brayton Cycle?

In an ideal Brayton cycle, the backwork ratio is the fraction of turbine work used to drive the compressor. It is defined as the ratio of compressor work to turbine work and typically falls within the range of 0.4 to 0.8.

This means that 40% to 80% of the turbine’s energy output is consumed by the compressor. Although the compressor requires a significant portion of the generated work, the cycle still produces net power output, making it effective for applications like gas turbines and jet engines.

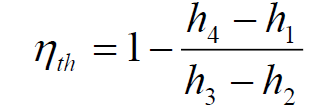

What is the thermal efficiency of the ideal Brayton cycle?

The thermal efficiency of an ideal Brayton cycle depends on the pressure ratio and combustion temperature. In a Brayton cycle integrated with fuel cells, the maximum pressure ratio is 32, and the maximum thermal efficiency reaches 82.2% at the lowest combustion temperature. For a standard Brayton cycle (BC) operating at a higher combustion temperature, the efficiency is around 65.1%.

These values indicate that increasing the pressure ratio and optimizing combustion conditions significantly enhance the cycle’s efficiency, making it a key factor in gas turbine and power generation applications. The thermal efficiency (η) of an ideal Brayton cycle is defined as the ratio of the net work output to the heat input:

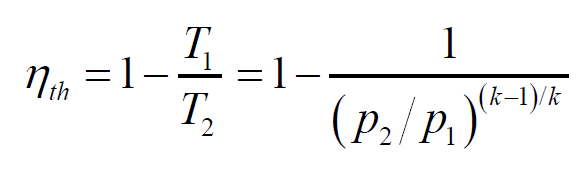

What is the ideal cold air standard for the Brayton cycle?

This assumption simplifies the analysis by treating the working fluid (air) as an ideal gas with constant specific heat. For an ideal Brayton cycle with a cold air standard, the thermal efficiency is calculated using the formula:

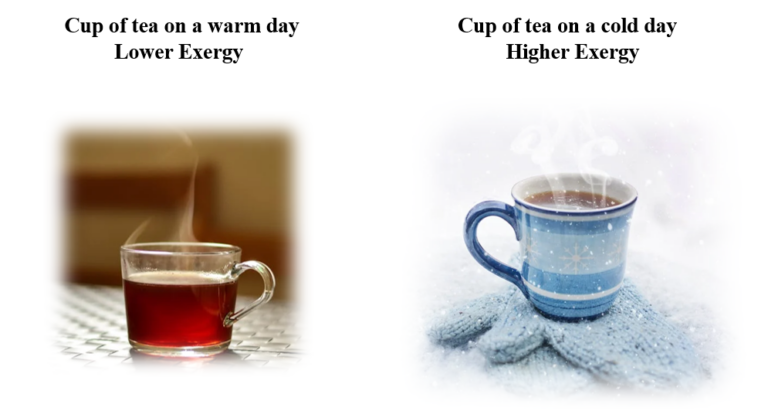

What is an ideal refrigeration cycle?

An ideal refrigeration cycle is a thermodynamic process that transfers heat from a low-temperature area (such as inside a refrigerator) to a high-temperature area (such as the surrounding kitchen), requiring work input to drive the process. Since heat naturally flows from hot to cold, refrigeration systems use mechanical work to reverse this flow, making them the opposite of heat engines.

There are different types of refrigeration systems, including:

- Refrigerators – Remove heat from the air inside an enclosed space.

- Air Conditioners – Extract heat from an occupied space to cool it.

- Heat Pumps – Transfer heat into an occupied space for heating.

- Chillers – Remove heat from water for cooling applications.

An ideal refrigeration cycle can be considered an ideal heat engine operating in reverse, often modeled as a reverse Carnot cycle. Refrigeration cycles are commonly categorized into vapor compression, vapor absorption, gas cycle, and Stirling cycle types, with vapor compression being the most widely used in practical applications.

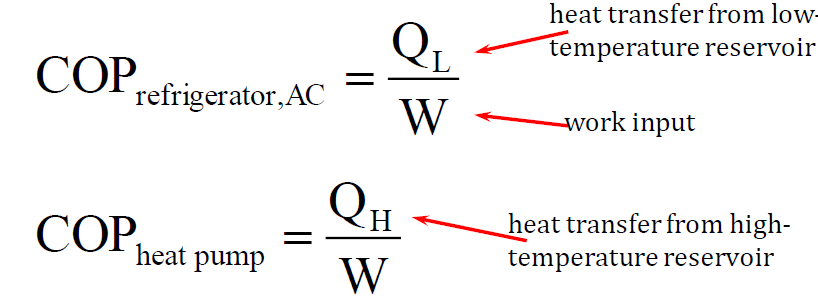

What is the coefficient of performance for the refrigeration cycle?

In refrigeration cycles, the coefficient of performance (COP) is used instead of thermal efficiency to measure how effectively a system transfers heat. It is defined as the ratio of useful energy transfer (heat removed from a low-temperature space) to the work input required to drive the cycle:

A higher COP indicates a more efficient refrigeration system, meaning it requires less work to remove the same amount of heat. The COP varies depending on system design and operating conditions but is a crucial metric for evaluating the efficiency of refrigerators, air conditioners, and heat pumps.

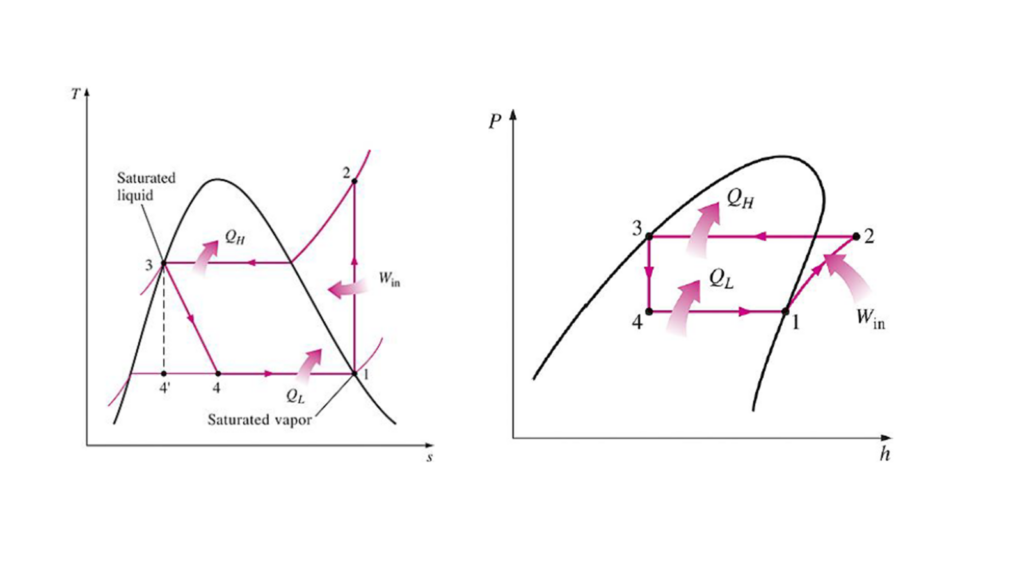

Vapor-Compression Cycle: Cooling Systems

The vapor-compression cycle is the most widely used refrigeration cycle in air conditioners and refrigerators. It consists of:

- Isentropic compression in a compressor (1-2)

- Isobaric heat rejection in a condenser (2-3)

- Adiabatic expansion in a throttling device (3-4)

- Isobaric heat addition in the evaporator (4-1)

This cycle effectively cools spaces by transferring heat using phase changes of the refrigerant.

Conclusion

Thermodynamic cycles are the foundation of many modern technologies, from power generation to transportation and refrigeration. While the Carnot cycle provides an upper-efficiency limit, practical cycles like the Rankine, Otto, Diesel, Brayton, and vapor-compression cycles are designed for real-world applications, each optimized for specific performance needs. Understanding these cycles is crucial for improving energy efficiency and developing advanced thermal systems.

Magnificent site. A lot of useful info here. I’m sending it to a few friends ans also sharing in delicious. And of course, thanks for your effort!

Its like you learn my mind! You seem to understand so much about this, like you wrote the book in it or something. I think that you can do with a few to force the message home a bit, but other than that, that is excellent blog. A great read. I’ll definitely be back.