Why are cars so heavy?

Modern cars have become significantly heavier due to a combination of safety requirements, consumer demands, and technological advancements. Enhanced safety features, including reinforced body structures and advanced systems, have added considerable weight to vehicles. Additionally, comfort and convenience features such as air conditioning, infotainment systems, and electric windows further contribute to mass increases.

The integration of pollution control technologies, the growing preference for larger vehicles, and the continued use of traditional heavy materials like steel also play a role. While lighter materials such as aluminum and magnesium are being introduced, the transition remains gradual. Moreover, the addition of technical features and shifting economic and demographic factors have led to a rise in vehicle weight, affecting fuel efficiency, particularly in urban driving conditions. As a result, the modern automobile has become heavier.

Why do cars keep getting bigger and heavier over time?

It seems like each year that goes by cars seem to get bigger and heavier! The average weight of a recently purchased vehicle in the United States reached 4,329 pounds in 2022. This figure exceeds the 1980 average by over 1,000 pounds and reflects an increase of approximately 175 pounds within the last three years alone. In essence, more than a third of the average weight of an American car has been added in the past four decades, a trend further intensified by the shift to electric vehicles (BEVs).

Conventional automobiles like the Honda Accord, Toyota Camry, and Ford Taurus have experienced substantial weight increases, ranging from several hundred to as much as 650 pounds, over the past two decades. Similarly, sport sedans including the BMW 3 Series, Mercedes-Benz C-Class, and Audi A4 have undergone comparable weight gains, reaching up to 550 pounds in certain cases. Even the relatively compact Toyota Corolla and Honda Civic, known for their lighter builds, have seen significant increases in curb weights. This trend is attributed to consumer preferences for safety, comfort, and convenience features, shaping the evolving landscape of vehicle specifications in recent decades.

How is the weight of a car measured?

The weight of a car is typically measured using a weighbridge, a large-scale platform designed for weighing vehicles. When a car drives onto the weighbridge, it provides an accurate measurement of the gross vehicle weight (GVW), which includes the vehicle itself, passengers, cargo, and fuel. However, among the various weight measurements listed in a vehicle’s specifications, the curb weight is often the most useful.

What is a Vehicle Curb Weight?

Curb weight refers to the total weight of a vehicle when equipped with all standard features, including motor oil, coolant, washer fluid and a full tank of fuel, but without passengers or cargo. It plays a crucial role in vehicle performance, as it directly impacts fuel efficiency, acceleration, and rolling resistance.

Heavier vehicles require more energy for movement, leading to increased fuel consumption and higher CO2 emissions. This makes curb weight an essential factor in vehicle design, particularly in balancing safety, comfort, and environmental impact. U.S. vehicles generally have higher curb weights than their European counterparts.

Why is the mass of a car important?

Attributing to Sir Isaac Newton’s first law of inertia (“an object at rest tends to stay at rest”), moving a heavier object (a vehicle) necessitates more power. Regardless of the engine type or fuel efficiency, the drivetrains need to work harder and consume more fuel when accelerating all this additional mass. This underscores the common understanding among sports car enthusiasts that weight poses a significant obstacle to performance.

A bigger and heavier car is better for vehicle crashworthiness, however, it is worse for vehicle fuel efficiency. For that reason, automotive engineers are constantly balancing vehicle crash performance and overall vehicle mass/efficiency.

When did cars start becoming heavier?

Mild steel was able to provide a perfect balance of strength, formability, cost, and design flexibility that the automotive industry needed during its early years. It was not until after the gas shortages of the 1970s when the fuel economy standards were adopted in North America, that automakers began to look at increasing the efficiency of their vehicles [4]. However, this trend would not continue for long.

The surge in vehicle weight gain initiated in the 1980s is partly attributed to the introduction of new safety regulations. The inclusion of airbags, emphasis on crash-test ratings, and the adoption of sturdier body-in-white structures contributed to the increase in the weight of vehicles. Simultaneously, advancements in construction techniques and the utilization of stronger materials diminished engineers’ concerns about weight, leading to a shift where efficiency became less of a primary focus. This lack of focus on vehicle mass is not good for the environment, it’s not good for resources.

Added Weight Due to Comfort and Convenience Features

While convenience features are not a recent addition to automobiles, modern vehicles, including entry-level models, are equipped with an abundance of features aimed at enhancing driving ease and convenience. Today’s consumers expect a full array of power and luxury amenities (such as heated/cooled seats, sound deadening, and rear climate control) along with the latest technologies (Bluetooth connectivity, infotainment systems, real-time navigation). Once again, the compromise for increased convenience is the added weight—sometimes quite substantial.

The impact of vehicle size on mass?

Cars have been getting heavier and larger due to a combination of safety regulations, consumer preferences, and industry incentives. The inclusion of safety features such as airbags, crumple zones, and reinforced structures has necessitated larger vehicle designs, while consumer demand for spacious interiors, luxury features, and increased cargo capacity has further driven growth in size. Additionally, regulatory frameworks often impose less stringent fuel economy requirements on larger SUVs and trucks, making them more attractive for manufacturers to produce. This trend, rooted in the perception that “bigger is safer,” has led to a steady increase in vehicle size and weight since the late 1970s.

Heavier Vehicles Don’t Always Offer More Protection in a Crash

There’s a limit to how much extra mass improves safety. A new study by the IIHS sheds light on this issue with concrete data. As vehicle safety systems—such as airbags, automatic emergency braking, and advanced bumper designs—have improved across the board, the impact of vehicle weight on occupant safety has diminished. In other words, modern crash prevention and mitigation technologies mean that simply being in a heavier vehicle doesn’t provide the same safety advantage it once did.

The study analyzed data from the Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) between 2011 and 2022, focusing on crashes involving vehicles that were 1 to 4 years old and resulted in at least one driver fatality. Of the 440,604 total traffic fatalities recorded during that period, the researchers narrowed their focus to 9,674 relevant cases.

The findings reveal an interesting pattern. There’s a key weight threshold—around 4,000 pounds—where trends begin to shift. Below this weight, added mass offers a clear safety benefit to the driver, with only a slight increase in the fatality risk for the occupants of the other vehicle. For example, IIHS found that adding 500 pounds to a lighter car reduced the driver’s fatality rate by 17 points while increasing the fatality rate for the other vehicle’s driver by just one point.

However, once a vehicle surpasses the 4,000-pound mark, the trend reverses. Additional weight no longer provides extra protection for the driver but significantly increases the fatality risk for those in the other vehicle. This suggests that reducing the weight of the heaviest vehicles—such as large trucks and SUVs—could improve overall road safety.

How the Added Weight Incurs Costs

The additional costs associated with increased weight extend beyond the fuel pump or charging station, resulting in heightened fuel expenses. As articulated by Newton’s law (“an object in motion tends to stay in motion”), a heavier vehicle necessitates larger brakes, bigger tires, and a more robust suspension system— that ironically contribute to additional weight. Encumbered by this extra mass, these elements are prone to quicker wear and tear compared to their counterparts in lighter vehicles. For manufacturers, who must pass on heightened production expenses to consumers, oversized parts incur greater costs than their smaller equivalents.

To counterbalance the augmented mass, automakers have been compelled to enhance drivetrain power. Fortunately, advancements in engine technology have managed to offset the need for progressively larger engine displacements. For instance, a 1990 Toyota Corolla with a 1.6-liter engine and automatic transmission achieved an EPA mileage of 22 mpg city/30 mpg highway, while its 2010 counterpart, equipped with a significantly larger and more powerful 2.4-liter engine, maintains identical fuel economy. However, it prompts contemplation about the potential savings if every vehicle on the road could miraculously shed 500 pounds.

How does weight affect EV range?

As the United States accelerates its shift to electric vehicles (EVs), automakers have a heightened incentive to prioritize streamlining their vehicle lineups. The correlation between heavier vehicles, necessitating larger and costlier batteries, poses a financial challenge due to the combination of increased weight and reduced efficiency. Car manufacturers unable to effectively manage vehicle weight may find it challenging to remain competitive in terms of pricing and driving range.

As a result, there is a huge push to improve aerodynamic performance and reduce overall vehicle mass. on average a BEV is 33% heavier than a traditional internal combustion engine vehicle (ICE).

Unlike an ICE vehicle where the majority of the mass comes from the BIW in a BEV, the majority of the mass comes from the battery which is used to move the vehicle forward. If automakers are not careful this can quickly turn into a spiral, where the battery is enlarged to increase the vehicle range, however, this increased mass makes the vehicle less efficient. As a result, the battery needs to get larger to meet the range targets. Which results in the vehicle becoming heavier and less efficient once again.

How U.S. Regulations Have Driven the Rise of Larger, Heavier Vehicles

While regulations like CAFE standards were designed to improve fuel efficiency, they have inadvertently contributed to the growing size and weight of vehicles. Loopholes and incentive structures have encouraged automakers to prioritize larger vehicles, leading to safety concerns, higher fuel consumption, and increased emissions. This regulatory landscape presents an ongoing challenge in balancing vehicle safety, environmental impact, and efficiency, requiring policymakers to reconsider how size and weight regulations are structured in the future.

CAFE Standards and Vehicle Size

The Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) program, which sets fuel economy targets, has unintentionally encouraged manufacturers to build larger vehicles. The program calculates fuel economy standards based on a vehicle’s “footprint,” which is determined by the product of wheelbase and track width. Because larger vehicles face less stringent fuel efficiency requirements, automakers have an incentive to increase vehicle size to comply with regulations while maintaining profitability. This regulatory structure has led to a steady increase in the dimensions of cars, SUVs, and trucks.

The SUV Loophole and Its Impact

The “SUV loophole” has further accelerated the trend toward larger vehicles by allowing SUVs and trucks to be classified as “light-duty trucks.” Automakers have leveraged this loophole to build and sell larger, more expensive, less fuel-efficient vehicles while still complying with federal regulations. Additionally, tax incentives and consumer preferences have reinforced the demand for SUVs and trucks, making them the dominant choice in the U.S. market. The increasing prevalence of heavier vehicles has led to higher fuel consumption and greater emissions, complicating efforts to meet environmental and sustainability goals.

Enforced Safety Features Contribute to Increased Mass

In compliance with federal regulations, newer vehicles must incorporate a range of safety-focused technologies (such as anti-lock brakes, stability control, and tire-pressure-monitoring systems) and equipment (including airbags, laminated glass, and door intrusion beams). In addition every few years the federal government raises the bar for automakers to meet crash safety standards.

Although these safety measures are crucial, they inherently introduce additional weight to the vehicle. This may involve the integration of new systems or components and the reinforcement of existing parts to enhance the resistance to body structure deformation during a collision.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the increasing weight of modern vehicles is a multifaceted issue driven by safety regulations, consumer expectations, and technological advancements. While added mass contributes to crash protection, comfort, and convenience, it also impacts fuel efficiency, resource consumption, and even overall road safety. The shift to electric vehicles further complicates this trend, as larger batteries add significant weight, potentially reducing efficiency.

However, advancements in materials, aerodynamics, and vehicle design offer promising solutions to enable vehicle lightweighting. As the industry continues to evolve, striking a balance between safety, efficiency, and sustainability will be critical in shaping the future of automotive design.

References:

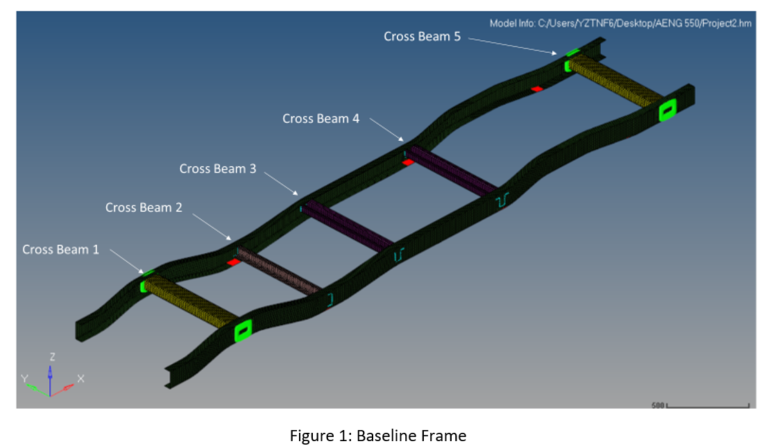

- Deb, Chapter 11 – Crashworthiness design issues for lightweight vehicles, Editor(s): P.K. Mallick, In Woodhead Publishing in Materials, Materials, Design, and Manufacturing for Lightweight Vehicles (Second Edition),Woodhead Publishing, 2021, Pages 433-470, ISBN 9780128187128, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818712-8.00011-2.

- Cischino, Elena, Et all. An Advanced Technological Lightweight Solution for a Body in White, Transportation Research Procedia, Volume 14, 2016, Pages 1021-1030, ISSN 2352-1465, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trpro.2016.05.082.

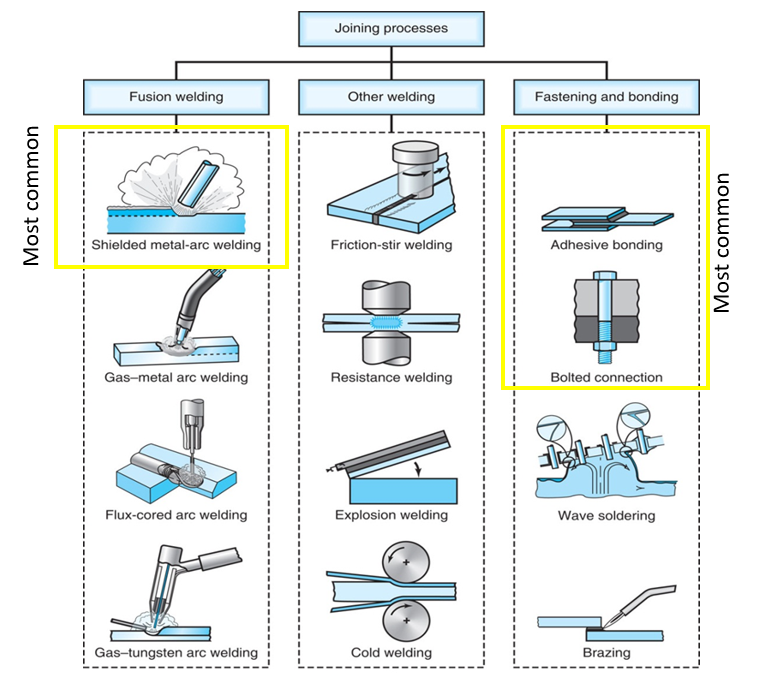

- Fang, Xiangfan and Zhang Fan, Hybrid joining of a modular multi-material body-in-white structure, Journal of Materials Processing Technology, Volume 275, 2020,116351, ISSN 0924-0136, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2019.116351.

- Horvath C.D., Chapter 2 – Advanced steels for lightweight automotive structures, Editor(s): P.K. Mallick, In Woodhead Publishing in Materials, Materials, Design, and Manufacturing for Lightweight Vehicles (Second Edition), Woodhead Publishing, 2021, Pages 39-95, ISBN 9780128187128, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818712-8.00002-1.

- Kumar, Kiran Et all. State of the Art on Automotive Lightweight Body-in-White Design, Materials Today: Proceedings, Volume 5, Issue 10, Part 1,2018, Pages 20966-20971, ISSN 2214-7853, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matpr.2018.06.486.

- Mallick, P.K. Chapter 8 – Joining for lightweight vehicles, Editor(s): P.K. Mallick, In Woodhead Publishing in Materials, Materials, Design, and Manufacturing for Lightweight Vehicles (Second Edition), Woodhead Publishing, 2021, Pages 321-371, ISBN 9780128187128, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818712-8.00008-2